THE ADVOCATE 389

VOL. 80 PART 3 MAY 2022

segregate laypeople from professional users of courts “for fear of ‘contamination’”

28), and even court robes (originally worn “when lawyers were

granted the right to appear in law courts … as a symbol of that privilege”29),

serve to visually exclude self-represented litigants, making them appear as

uninvited guests in courts designed by and for lawyers. The excessive use

of heightened language and class-based honorifics can also ostracize lay

users (even finding the right word for the judge is hard with, traditionally,

such a long list of options: “Your Worship”, “Your Honour”, “My Lord”, “My

Lady”, “Master”, etc.).30 Presumably such features have, despite some recent

evolution, endured because we believe them to promote the courts’ legitimacy.

However, they may in fact do the opposite, causing lay litigants to

feel excluded, disempowered and perpetually “on the outside” of the system.

As Oxford law professor and courtroom architecture expert Linda

Mulcahy, explains: “Just as the architecture of many courts is designed to

engender awe in the court user, so too can surroundings form part of a

degradation ritual”.31 Traditional courtroom architecture and rituals can

have a “a paralysing effect on those who are not regular users of the court

system and can serve to contribute to a ritualized stripping of dignity”.32

Virtual courts should not merely be a new way of accessing the courts of

1906; rather, they should employ technology as a tool to respond in new

ways to the needs of the people they are meant to serve. If meaningful

access to justice is the goal, and if our courts are to be spaces “by the people

and for the people”, then courts must privilege the needs, voices and experiences

of their lay users over the traditions to which the bench and bar

have become accustomed. As the Action Committee on Access to Justice in

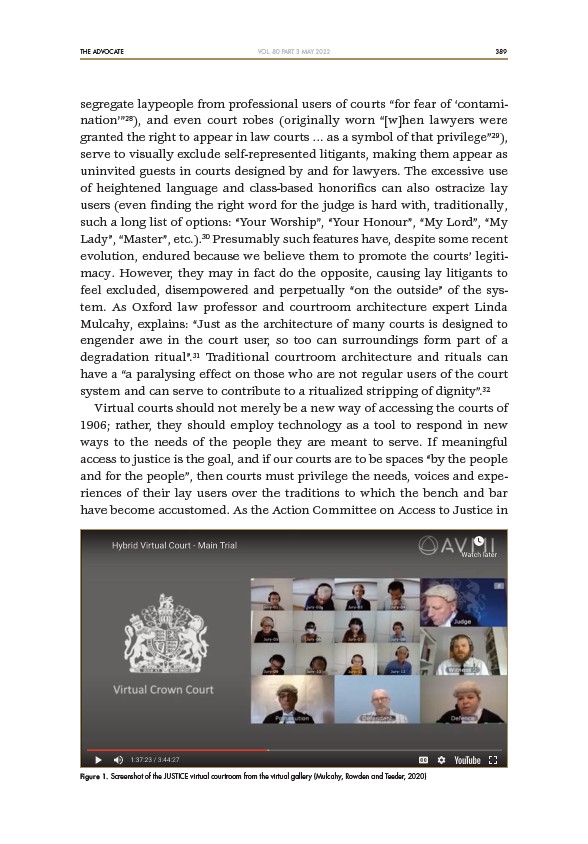

Figure 1. Screenshot of the JUSTICE virtual courtroom from the virtual gallery (Mulcahy, Rowden and Teeder, 2020)