846 THE ADVOCATE

VOL. 79 PART 6 NOVEMBER 2021

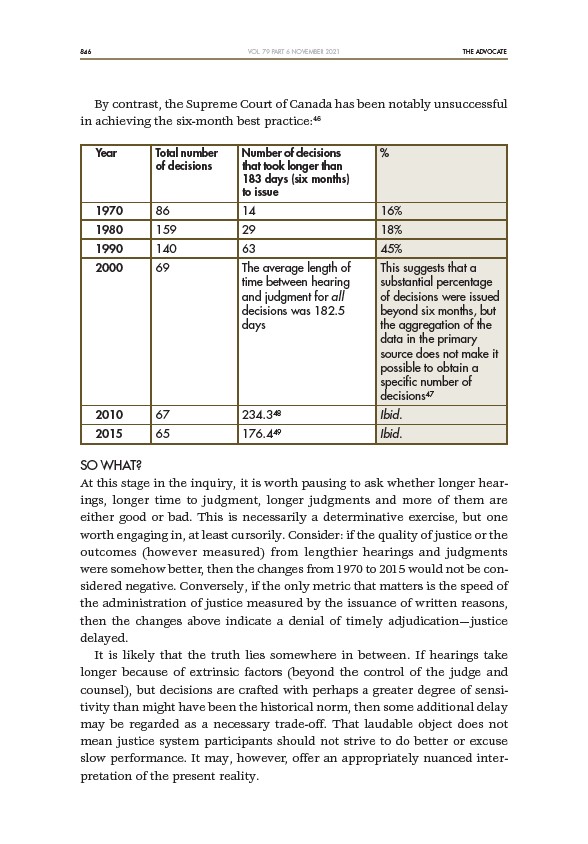

By contrast, the Supreme Court of Canada has been notably unsuccessful

in achieving the six-month best practice:46

Year Total number Number of decisions %

of decisions that took longer than

183 days (six months)

to issue

1970 86 14 16%

1980 159 29 18%

1990 140 63 45%

2000 69 The average length of This suggests that a

time between hearing substantial percentage

and judgment for all of decisions were issued

decisions was 182.5 beyond six months, but

days the aggregation of the

data in the primary

source does not make it

possible to obtain a

specific number of

decisions47

2010 67 234.348 Ibid.

2015 65 176.449 Ibid.

SO WHAT?

At this stage in the inquiry, it is worth pausing to ask whether longer hearings,

longer time to judgment, longer judgments and more of them are

either good or bad. This is necessarily a determinative exercise, but one

worth engaging in, at least cursorily. Consider: if the quality of justice or the

outcomes (however measured) from lengthier hearings and judgments

were somehow better, then the changes from 1970 to 2015 would not be considered

negative. Conversely, if the only metric that matters is the speed of

the administration of justice measured by the issuance of written reasons,

then the changes above indicate a denial of timely adjudication—justice

delayed.

It is likely that the truth lies somewhere in between. If hearings take

longer because of extrinsic factors (beyond the control of the judge and

counsel), but decisions are crafted with perhaps a greater degree of sensitivity

than might have been the historical norm, then some additional delay

may be regarded as a necessary trade-off. That laudable object does not

mean justice system participants should not strive to do better or excuse

slow performance. It may, however, offer an appropriately nuanced interpretation

of the present reality.